Marg stood in the yard taking frozen washing off the clothesline. It was late spring yet the cold of winter was still in the air. The clothes were as dry as she could get them today. The direction of the winds changed and she could smell the outhouse from down at the end of the yard. “Time to dig a new hole,” she thought.

Seemed like her whole life was boiling water, rubbing, scrubbing, wringing, hanging out the laundry and taking it down again and in between that, cooking for her family. Marg was grateful she could get laundry soap at the company store and didn’t have to make her own scrub soap out of lye and bacon grease like some folks.

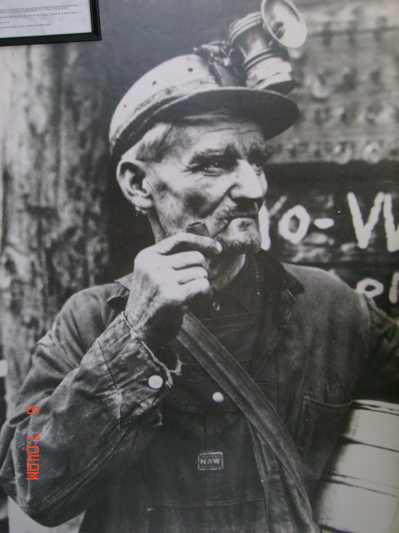

With five babies and with her husband Joe in the coalmines, there was no end to the dirty clothes or housework. Bath time was a chore because it took place in a washtub in the middle of her kitchen. Marg liked to imagine herself living in a home in a town with indoor plumbing. Her oldest girls could do some of the housework now, beating the coal dust out of the rugs, washing windows, sweeping floors and polishing the furniture.

Her children were in the yard with her. She kept her eyes on her children as the older ones ran around trying to catch one another, screamin’ “run sheep run.” ‘Run sheep run’ was what the children in these parts had called their game of tag for generations. Her children did not know where the name came from, as they had never seen their coal-mining father chasing a sheep at shearing time. But the game of ‘run sheep run’ reminded Marg of her grandpap on his farm at shearing time and she thought it was a good name for it.

She knew she should be grateful that in earlier years her husband’s father and grandpap saved enough of their miner’s pay to buy land in Carrolltown, Cambria County, Pennsylvania. What was it to her though? They owned the land. Not her husband Joe, even though Joe went into the mines starting in his twelfth summer, gave all his pay to his father, and helped to build every part of his father’s house. Today the land in Carrolltown between Main and Church streets housed three generations of her husband’s people, ten families with twenty babies between them. Down the street, Joe’s younger brother Turk kept enough laying hens to provide her family with eggs. This land got them through some hard times. Their lives were not like the folks in the coal company owned towns.

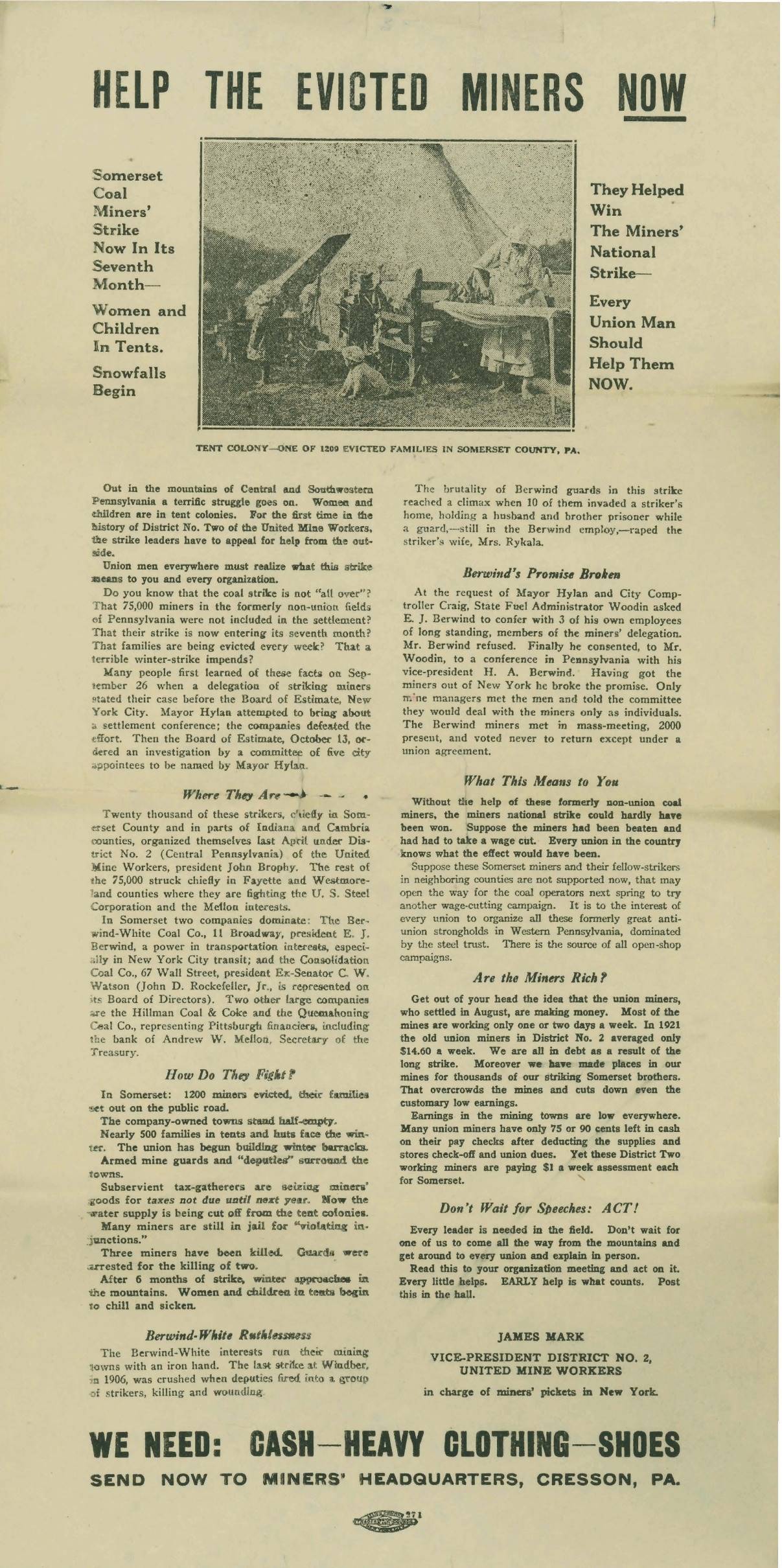

Patch was the name given to a company owned mining town. A patch consisted of rows of nearly identical houses, a company store, a church, a school and the mine. When the long strikes were on the families in the patch houses got thrown out of their homes. Mining families in the patches had to move into tents, chicken coops, beehive coke ovens, or whatever they could find. And women were having their babies in those conditions.

Marg’s baby doctor at the Miner’s Hospital in Spangler told her “Mrs. Lacey you are one of the lucky ones. All your babies are still alive. You know lots of babies are dying.” He added, “Babies in Cambria County die one out of ten, the highest infant death rate in the United States.” Marg did not believe the hospital had anything to do with why her babies were alive even though she did her lying in, there in the hospital, for her last four babies. When her mother and grandmother were still alive, she had her first baby just fine at her grandmother’s house with her mother at her side. The same way her mother and grandma had their babies. Marg saw the reasons babies were dying in Cambria County. A starving pregnant woman might have a dead baby no matter where she did her lying in. People were starving and babies were being born too soon, too small and sickly to live.