My Dad was a taciturn man

My Dad was a taciturn man. One of my most insidious memories of him is doing the washing-up after Sunday dinner. Dad washed the dishes in the kitchen sink, while I dried. Only sounds of soapy water slurping in the sink and clatter of crockery being stacked accompanied our thoughts. During the fifteen minutes it took to complete the chore, we washed-up in utter silence. Dad did not say a single word to me. This was repeated week after week. It perturbed me. What did it mean? His life – his thinking, his beliefs appeared opaque to me, his past encased in enigma.

Another vivid memory, when I was ten or eleven years old. Taken to the Financial Times where Dad worked in the bowels of a huge towering building – Bracken House - in London on Fleet Street. Strident rattling of printing presses, constant motion of newspapers carried above on conveyor belts, hot-metal typesetting machines dwarfing operators wearing visors hunched over keyboards amongst windowless cavernous space. High above I imagined editors, writers, and reporters typing and feeding this vast complex machine. But I could not comprehend Dad’s role.

I felt ambivalence to my father. I resented him for his addiction - sitting in the armchair, eyes glazed, absorbed in smoking a cigarette. But intrigued, tantalized by his reticence, where did he come from? I had seen Uncle Harold refuse to sit down to dinner with him. I tried to decipher the enigma. Where did he come from? Why did he hold these beliefs? I knew little of his early life, his working life. I had to know. Why did he leave school at fourteen years of age? Did he have a choice?

At school, I had difficult choices to make about my future. Should I stay at school or leave to become a plumber? Should I study English Literature or Maths and Physics? Who am I? What do I want? Perhaps Dad’s experiences could provide insight and help in the decisions. But all gestures were rebuffed.

In other ways, I tried to drill through the shell that surrounded his past. I raided his wardrobe rehabilitating a tweed overcoat from the forties that I wore on nights’ out with my mates; looked through the mementoes he kept and found the hockey puck from the 1948 Olympics. The emotional distance between us seemed too far to bridge, and neither of us had the desire to do so.

When Dad retired we spent time together and got on well. But underlying our communication there was always my seemingly insatiable need to know more about his enigmatic past. In 1993, I interviewed him sitting in front of a video camera. For most of the interview distracted he flicked through the pages of a magazine on his lap. But the stories he told, for instance, about walking in the middle of the night during the blitz twenty-five miles from South London across the river Thames to the East End to court my mother; while fascinating did not satisfy my needs ossified in adolescence.

Ten years ago Dad died and left an untidy pile of old photographs, crumpled certificates and letters. I did not have time to sort through the pile. A few years further on contradictions in late-stage capitalism popped the technology bubble of Silicon Valley. I fell to my knees, forced to examine my working life and make decisions about what I wanted to do. I had the time to look at the detritus Dad left, spurred on by my dilemma.

I found out that David Henry - my great grandfather, David Edgar - my great uncle, and Arthur Charles - my grandfather - were all plumbers of one sort or the other. I came from a family of plumbers. But it raised the question why did Dad not become a plumber and follow his father? Also, why, when I embarked on plumbing at school, did he never mention the family history in plumbing?

Delving deeper I found a series of letters Dad had kept that illuminated the launch of his working life. My Dad - Percy Victor Cooley - born 1916 and raised at 124 Falmouth Road, Southwark, an inner London borough south of the river Thames, close to the Elephant and Castle. He grew up in a period of political upheaval, still in the shadow of the Great War that decimated the population of young men. 1918 saw the bursting onto the scene of the Labour Party as a political force in Britain; a movement that gathered strength so rapidly that within six years the Party was in office. Class became a major source of social and political cleavage. Middle and upper classes reeled under the shock of a newly politicized and assertive working class. Women joined the electorate, finally on the same terms as men. In 1926, there was a General Strike in Britain when the majority of workers across the country stopped work for nine days in solidarity with the miners. Winston Churchill, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Tory Government of the time, led the upper and middle-class confrontation with the strikers.

Percy’s narrative starts with a letter addressed to my grandfather Arthur Cooley dated 25th September 1930:

“Dear Mr. Cooley, With reference to the call of your Son on Saturday last, we are quite willing to take him as a messenger boy when 14 years of age or as soon after that as he leaves school. If after a few months trial we find that he is suitable for apprenticeshap (sic) to Process Engraving we will be willing to keep him as a messenger then give him if feasable (sic) a chance in one of the departments; either Photography, Etching, Line etching or Printing as the case may be. I am glad to say that he gives promise of being a suitable lad, but for the moment it is better to commit neither him or ourselves to the trial venture.

Yours faithfully

Nelson R Bird – Managing Director, The Arc Engraving Company “

Note the caution in the letter, for good reason, as Dad would say pointing to the sky, “it looks black over Will’s Mum’s”. There were black clouds to the economy. They heralded the beginning of the Great Depression; unemployment in England had begun to rise, business conditions became difficult.

A letter dated 21st October 1930, five days before Percy’s 14th birthday, from the Rockingham Street School titled testimonial, read:

“I am pleased to testify to the excellent conduct and character of Percy Cooley, who has been a diligent scholar, reliable and trustworthy in every way and has set a fine example to the other boys. I can recommend him and he has my very best wishes.”

The following year, dated 21st March 1931 a letter to Arthur Cooley read:

“Mr. Bird – (Managing Director Arc Engraving Company) - desires me .. to inform you that your boy is giving every satisfaction and short of an absolute promise we are hoping to be able to apprentice him when he is 16.”

Next year a letter to Arthur dated, 2nd November 1932, a week after Percy’s 16th birthday, says:

“Mr. Bird desires me to apologise for not having answered your letter, he was hoping to have been able to settle the matter with his fellow Directors ere this. He hopes to do so in the next day or so and will then write you.”

Arthur must have been getting anxious about the future of his youngest son, Percy. Subsequently Arthur received a letter dated 8th December 1932 from Nelson R Bird, it read:

“I am sorry to have delayed giving you a definite answer .. as to apprenticeship for your boy. The fact is that conditions are altogether different now to what they were when your son came here as a messenger and there is an arrangement whereby, owing to so many being out of work, that for a time no new apprentices should be taken.

However, I hope that we have overcome those difficulties in your son’s case…”

1932 was the peak of the Depression with extremely high levels of unemployment in London and even more devastating conditions in the north of Britain. But the difficulties must have been overcome because I found an Indenture of Apprenticeship dated 22nd December 1932, signed by Percy, the Apprentice, Nelson Bird, the Master and Arthur Cooley, the Parent.

An indenture is a legal document signed by apprentices and their masters to agree the conditions of an apprenticeship.

The agreement reads:

“Whereas the apprentice has agreed to bind himself and the Master has agreed to accept him … the Master will take and receive the Apprentice as his apprentice for the term of five years to be computed from the first day of November 1932. .. and .. will .. teach and instruct or cause to be taught and instructed the Apprentice in the trade or business of Process Engraving. "

Apprenticeship dates back to the craftsman guilds of medieval times. It is surprising to see how much of the formal Indenture of Apprenticeship used in the sixteenth century survives in the twentieth-century form. Indentures from the 19th Century included passages such as,

“he shall not commit fornication nor contract matrimony within the said term, shall not play at cards or dice tables, or any other unlawful games whereby his said master may have any loss,”

The indenture sets out the wages for Percy over the next five years starting at 15 shillings a week, rising to 40 shillings in the fifth year; and his hours of work – from 8:30 to six Monday to Friday and from 8:30 to 12:30 on Saturday. It placed a burden on the apprentice to “faithfully honestly and diligently serve the Master and obey and perform all his commands.” And “He shall not absent himself from his Master’s service unlawfully but shall in all things conduct himself as an honest and faithful apprentice ought to do.” The parent –Arthur – was required: “ at his own expense provide the apprentice with sufficient board clothing and lodging and all other necessities during the said term. “

A letter from Reverend Dickens at St Matthews, Southwark dated 23rd December:

“ I was delighted to get your letter to-day and to know that Percy has made such progress. I have often thought that he would find the early stages in the firm rather trying but apparently he has put his back into it and done well. It seems that there is no need to urge him to take a real interest in the work. If all I hear is true he really is lucky to be learning a trade which is going to be a stand-by all his life. Parents are simply bewildered as to what to do with their boys and you must feel very happy that ways have opened for yours. It was very nice of you to write to me and I appreciate the kindly thought very much. May God bless everybody at 124 this Christmas.”

What a gift for Christmas it must have been to Percy and his father to have Percy established as an apprentice at the Arc Engraving Company on Farringdon Street, just round the corner from Fleet Street.

Amongst the mound of photos I discovered one photograph that captured my attention. It shows a group of thirty five men dressed in their finest suits and ties sitting and standing outdoors on grass with trees and bushes in the background. As I looked closer I noticed a young Percy at the back of the group his head just visible. I realized this was a picture taken at one of the annual outings of his employer – Arc Engraving. Here in microcosm is a visual depiction of the class structure of the time. Sitting on a bench in front and center were four men. In the middle were two older men dressed in high quality single-breasted suits with waistcoats, self-satisfied smiles underneath felt Homburgs. These hats were popular in the thirties with the elite, being first worn by the young dashing British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. Presumably the two men are the Managing Directors of Arc Engraving – Nelson R. Bird and George G. Huggins. Beside them on either side are the foremen and arrayed behind are the workers. A few tentatively smile, some wear cloth-caps or a trilby, the younger apprentices at the back. To one side in contrast stands a young fellow in a loose light-colored double-breasted suit holding a raincoat over his arm, his other hand in his pocket, flower in lapel.

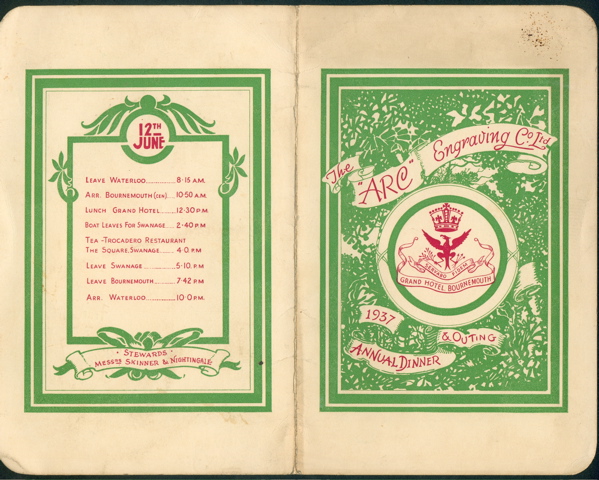

Percy had kept the cards for the annual dinner and outing of the Company from 1934 to 1939, usually on a day in June. Perhaps, Percy worked on the engraving for the cards. They are engraved on heavy stock and feature elaborate designs displaying the handiwork of the company, setting out the itinerary and menu for the day at the seaside. For example, from the outing in 1935: leave Waterloo, the main London railway terminus for the south coast of England, at 8:15 am and arrive in Bournemouth at 10:51 am. Lunch at the Grand Hotel; the menu for dinner includes specialties such as Roast Surrey Chicken and Bacon with Bread Sauce. The stewards for the day are listed, their duty would be to usher the men to and from railway carriages and omnibuses so no one gets left behind. These were halcyon summer days where workers and bosses could enjoy a jaunt and a break from work. Meanwhile dark clouds began to gather across Europe.

Five years later, in 1937 the apprenticeship was complete. A handwritten letter dated 13th November 1937 with an address from The Tooting Constitutional Club.

Dear Mr and Mrs Cooley,

I was very agreeably surprised on Saturday to receive such a nice and useful gift and I sincerely thank Percy for it. Now in regard to Percy I must say that I am of the opinion that he will turn out quite a 1st Class Craftsman. In his early days I liked his application to the Business, and his attention to the Bolt Court School and I feel that he has the ability to take over when some of us Old ones are things of the past.

I appreciate very much your letter. Thanking you once again, I am

Yours sincerely

T. Mitchell

I don’t know who T. Mitchell was but I assume he was instrumental in obtaining the apprenticeship for Percy. He had signed Percy’s Indenture as the Apprentice’s witness.

I discovered a handwritten note on the back of the Indenture:

“This indenture has been faithfully carried out and Percy Victor Cooley has at all times been a very good apprentice. His attention to learning his profession has been at all times very good and now is well qualified as a journeyman; while his general conduct has always been most satisfactory.

We wish him every success in the future.

Signed Nelson R Bird”

Percy seemed poised for a successful career as a journeyman Engraver but history intervened. For Dad it ended with a letter dated 28th June 1940:

“Dear Mr. Cooley

We regret to have to inform you that owing to the obvious state of business it is a sheer necessity to give you a weeks’ notice.

Thanking you most heartily and sincerely for past services, and trusting that your period of unemployment will be very short …”

In the previous year war had been declared against Germany, that month Winston Churchill had become Prime Minister and one of his first actions was to ban strikes. Percy had applied to be added to the register of Conscientious Objectors.

After the war Percy joined St Clements Press in Fleet Street which printed the Financial Times newspaper. He joined the chapel, that is the local branch, of the union and became the Treasurer. The post-war boom in Britain stoked the leap-frogging process of innovation and in 1963 the technology Percy trained in became obsolete. The trade he learned was not going to be a stand-by for all his life. St Clements Press made Percy redundant.

© 2007 Keith David Cooley